Learning Health Systems

From Chapter 1 of the "Textbook of Digital Health" by Dr Chris Paton:

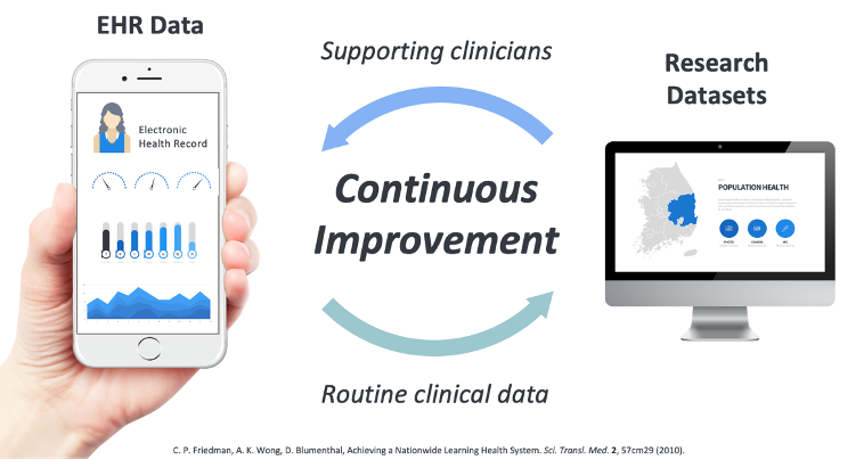

In 2007, a group of healthcare leaders from around the world gathered at a workshop organised by the US-based Institute of Medicine to discuss how the digitisation of healthcare could be best utilised to improve the health of patients. From that workshop, a new concept emerged, that of the “Learning Health System”. The idea is quite simple at its core: Use the data routinely generated by DHTs, such as Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems, to inform decision-making at multiple levels (clinic, hospital, region, nation, worldwide) to enable the healthcare system at each level to learn and improve. For example, data from an outpatient clinic could show that the patient mix had changed in recent years and an adjustment to the staffing was needed to better meet the needs of patients. At a higher level, the data from multiple hospitals’ EHR systems could be used to identify the outcomes of patients who had been enrolled on a clinical trial.

Learning healthcare systems have the potential to accelerate the adoption and influence of evidence-based medicine (the idea that clinical decision-making should be informed by the “current best evidence” rather than expert or personal opinion). Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has traditionally primarily used randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) to generate research evidence which is then synthesised through a process of systematic review and meta-analysis before being translated into evidence-based clinical guidelines that doctors and allied healthcare professionals can use to treat patients. Several significant challenges have emerged as this approach has gathered steam. Not least of these is the cost and inconvenience of conducting large-scale RCTs. Many treatments in medicine have quite small effects (perhaps only successfully treating only a small percentage of patients who take them). These small effects can add up to large numbers of real people if enough people take the medications but detecting these small beneficial effects requires thousands of people to participate in trials, with half the participants receiving the new treatment and the other half being treated with a placebo. These trials can take years and vast sums of money to conduct. Perhaps then, by conducting trials using EHR systems for recruiting, allocating and following up patients, an LHS can rapidly advance our knowledge about which treatments work best and who should be taking them. This latter point may be enabled by another new development, personalised medicine. By linking a patient’s genome with the data in their EHR (a so-called “digital phenotype”), we could start to draw conclusions on how different genetic combinations influence how effective different medications are. Perhaps in the future, the types of drugs we are prescribed (and their dosages) will be determined by a genetic blood test prior to treatment.

Paton, C (2024). Textbook of Digital Health.